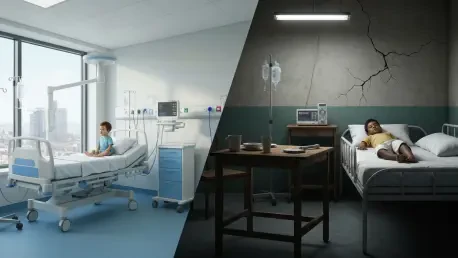

A comprehensive global study has brought to light the profound and deeply concerning disparities in survival rates among children diagnosed with cancer, revealing a stark divide that correlates directly with a country’s socioeconomic development. The research, which aggregates data from numerous countries, underscores an urgent global health crisis where a child’s chance of surviving cancer is overwhelmingly determined by their geographic location. The findings paint a clear picture of two vastly different realities: one in high-income nations where childhood cancer is increasingly a manageable disease, and another in low- and middle-income countries where it remains a frequent death sentence. This investigation moves beyond mere statistics to uncover the systemic failures in healthcare delivery that create this life-or-death lottery, pointing not to a difference in the disease itself but to a critical gap in access, resources, and infrastructure that leaves the world’s most vulnerable children behind in the fight for their lives.

The Scope of the Global Divide

The central subject of analysis is the vast chasm in survival outcomes for pediatric cancer patients between affluent and less-developed regions. Sobering statistics establish the scale of the issue: worldwide, more than 200,000 children under the age of 15 are diagnosed with cancer each year, and of those, nearly 75,000 succumb to the disease. A key theme is the paradoxical nature of this mortality burden. While childhood cancer is more commonly diagnosed in Europe and North America, the majority of deaths occur in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. This points not to a difference in the disease itself, but to a systemic failure in the delivery of care. The overall survival figures are a testament to this gap. In high-income countries, the five-year survival rate for children with cancer exceeds 80%. In stark contrast, the global average is a mere 37%, a figure heavily weighed down by the poor outcomes in less-developed nations, where survival can plummet below 40%, leaving countless families without hope.

To quantify these differences with greater precision, an international study was conducted using data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). This extensive analysis, part of the Cancer Survival in Countries in Transition (SURVCAN-3) project, examined data from nearly 17,000 children across 23 countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The results revealed striking variations in survival for specific types of cancer, providing concrete examples of the life-or-death disparities. For instance, in the case of central nervous system tumors, the three-year survival rate in Puerto Rico is almost 80%, approaching the standard seen in high-income nations. However, for the same diagnosis in Algeria, the survival rate is a tragically low 32%. The disparity is even more pronounced for leukemia, one of the most common childhood cancers. In Puerto Rico, the survival rate reaches an impressive 90%, whereas in Kenya, it stands at a devastating 30%. This 60-percentage-point difference for the same disease highlights the profound impact of non-biological factors on patient outcomes.

Systemic Failures and Infrastructural Barriers

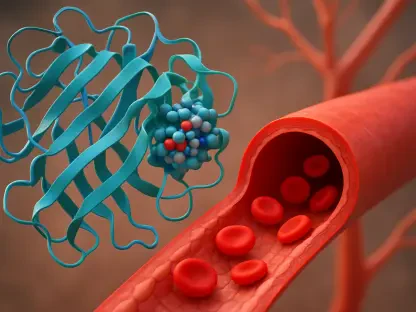

The overarching trend identified in the research is that these survival variations are not random but are inextricably linked to a country’s level of development and the robustness of its healthcare system. The analysis identifies several key factors that contribute to this deadly gap. First is the prevalence of late diagnosis, where cancers are not identified until they have reached advanced stages, making them far more difficult to treat successfully. Second is the issue of limited treatment options; many low- and middle-income countries lack access to specialized pediatric oncology centers, essential medicines, and advanced technologies like radiation therapy. Third, even when treatment is available, there are significant challenges related to the suboptimal quality of care, stemming from a shortage of trained healthcare professionals, inadequate infrastructure, and a lack of standardized treatment protocols that are common practice in more developed health systems.

Furthermore, the study highlights a fundamental infrastructural problem that hampers efforts to address the crisis: the absence of reliable data. Many countries lack comprehensive, population-based cancer registries. This deficiency makes it impossible to determine the true incidence and mortality rates of childhood cancer, effectively obscuring the full scale of the problem. Without accurate data, governments and health organizations cannot effectively plan interventions, allocate resources, or measure the impact of new policies, creating a cycle of informational blindness that perpetuates poor outcomes. This issue is compounded by treatment abandonment, a heartbreaking phenomenon where families are forced to discontinue care due to overwhelming financial costs, the logistical burden of traveling long distances to a treatment center, or a lack of social support systems, thereby nullifying any potential benefits of the limited care that might have been available.

Forging a Unified Path Forward

In response to these grave findings, the global health community has consolidated a clear and unified call to action. Dagrun Slettebø Daltveit, the study’s first author, states that the stark differences “underscore the urgent need to act.” This sentiment is echoed by the World Health Organization (WHO), which has established a specific and ambitious target through its Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer. The initiative aims to increase the global survival rate to at least 60% by the year 2030, a goal that requires a targeted and strategic approach to bridge the existing care gap. Dr. Isabelle Soerjomataram of the IARC emphasizes that the cornerstone of this strategy must be investment in population-based cancer registries. These registries are presented as the essential tool for enabling countries to measure their disease burden accurately and, crucially, to track their progress in childhood cancer control over time, turning data into a life-saving instrument for policy and planning.

The main findings of the SURVCAN-3 study were therefore twofold, serving not only as a detailed, data-driven confirmation of the extreme survival disparities but also as a foundational benchmark for monitoring future improvements. The research demonstrated unequivocally that many more lives could be saved through the implementation of proven strategies, namely ensuring early diagnosis and providing access to effective, standardized treatment protocols. Ultimately, the investigation concluded that achieving the WHO’s 2030 goal was critically dependent on a sustained, dual investment. This involved strengthening cancer registries for data-driven oversight while simultaneously building the broader health infrastructure required to deliver consistent, high-quality care to every child, regardless of their birthplace. The roadmap to closing this devastating gap was laid out, shifting the focus from identifying the problem to actively implementing its solution.