Across the globe, mental disorders stand as a formidable public health challenge, contributing to significant disability, premature mortality, and crushing economic burdens on both patients and healthcare systems. In China, where the lifetime prevalence of these conditions exceeds 16%, the financial toll of inpatient care often drives families into severe distress. Traditional payment models, such as fee-for-service (FFS), have long worsened this issue by encouraging prolonged hospital stays and unnecessary treatments, inflating costs without necessarily improving outcomes. To tackle this systemic problem, a groundbreaking per diem payment (PDP) reform was rolled out in January 2022 in City W, a less economically developed region in central China. This innovative approach, which provides a fixed daily reimbursement rate based on hospital level and length of stay, aims to curb overutilization and bring much-needed relief to strained budgets. A recent study from Huazhong University of Science and Technology, published in a leading health services journal, offers a detailed look at how this reform has reshaped the landscape of psychiatric care in primary and secondary hospitals, which serve the majority of patients in the area. While the findings point to substantial cost reductions, they also spark critical questions about service efficiency and the potential risks to quality of care, making this a pivotal moment for healthcare policy in resource-constrained settings.

Financial Impact of Per Diem Payment

Cost Reductions and Economic Relief

The introduction of the PDP reform in City W marked a turning point in managing the escalating costs of psychiatric care, with data revealing a consistent downward trend in hospitalization expenses. Researchers found a significant monthly decrease of 4.4% in average costs at primary hospitals and 2.1% at secondary facilities following the reform’s implementation. Even more striking was the immediate impact in secondary hospitals, where costs plummeted by 36.1% right after the rollout in early 2022. This sharp reduction suggests that the fixed daily reimbursement model effectively dismantled the financial incentives for overutilization that plagued the FFS system. For patients, often burdened by the high price of long-term mental health treatment, this shift represents a critical step toward affordability. Beyond individual relief, the broader healthcare system also benefits as resources are allocated more wisely, potentially freeing up funds for other pressing needs in under-resourced regions like City W.

Equally impactful was the effect on out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses, which directly affect patients’ ability to access care without sinking into financial ruin. Post-reform, primary hospitals saw an immediate 33.5% drop in OOP costs, followed by a steady monthly decline of 3.4%, while secondary hospitals recorded a consistent 4.2% monthly reduction. This alleviation of direct costs has been particularly meaningful for low-income families, who often struggle to afford sustained psychiatric treatment. Additionally, reimbursements from basic medical insurance (BMI) mirrored this trend, decreasing by 4.5% monthly in primary hospitals and 2.0% in secondary ones, with an initial 41.2% drop in the latter. Such reductions indicate a lighter load on public insurance systems, which could enhance sustainability. However, the long-term implications of these savings remain under scrutiny as policymakers assess whether they compromise essential services.

Risks of Underfunding Care

While the financial benefits of PDP are evident, a lingering concern is whether these cost-saving measures might inadvertently restrict access to necessary treatments for mental health patients. The fixed daily reimbursement rates, while effective in curbing excess spending, could pressure hospitals to prioritize fiscal efficiency over comprehensive care. In cases of chronic mental disorders, which often require extended or intensive interventions, such constraints might lead to shortcuts in treatment plans. Hospitals, particularly those in economically challenged areas like City W, may find themselves rationing resources or limiting specialized services to stay within budget. This potential for underfunding raises a red flag, as inadequate care could worsen conditions, ultimately driving up costs through emergency interventions or readmissions down the line.

Balancing the dual goals of fiscal responsibility and adequate patient care remains a formidable challenge under the PDP framework. The risk of under-treatment is especially acute for individuals with complex psychiatric needs, where tailored therapies and prolonged monitoring are often non-negotiable. If hospitals face penalties or reduced reimbursements for extended stays, there’s a chance that patients could be discharged prematurely, before achieving stability. This scenario underscores the importance of establishing safeguards to ensure that cost controls do not erode the foundation of effective mental health care. Policymakers must consider mechanisms such as tiered reimbursement adjustments or supplemental funding for severe cases to prevent such outcomes, ensuring that the pursuit of savings does not come at the expense of vulnerable populations.

Service Efficiency Under PDP Reform

Mixed Results on Length of Stay

One of the central aims of the PDP reform was to enhance service efficiency by reducing unnecessary hospital stays, a persistent issue under the FFS model that incentivized prolonged admissions for higher revenue. However, the study’s findings on average length of stay (ALOS) paint a nuanced picture of the reform’s impact. In primary hospitals, no statistically significant change in ALOS was observed after the PDP rollout, indicating that longstanding clinical practices or patient care protocols may be resistant to change driven solely by payment structures. This lack of shift suggests that simply altering reimbursement methods might not be enough to overhaul deeply ingrained habits in resource-limited settings, where other systemic factors could play a role in determining hospitalization durations.

In contrast, secondary hospitals displayed a more promising, albeit still inconclusive, trend following the reform. Prior to PDP, these facilities saw ALOS increasing by 1.384 days per month, reflecting the FFS-driven tendency to extend stays for financial gain. Post-reform, a downward trend emerged, though it did not reach statistical significance. This partial progress hints at PDP’s potential to encourage more efficient resource use, yet the lack of definitive results points to the influence of historical cost-based reimbursement structures that may still afford hospitals some flexibility in managing stays. The disparity between primary and secondary hospital outcomes underscores the complexity of achieving uniform efficiency gains across different levels of care, particularly in regions with varying operational capacities.

Challenges in Changing Provider Behavior

Altering entrenched provider behavior, shaped by years of operating under the FFS model, has proven to be a tougher hurdle than anticipated in the wake of PDP implementation. Hospitals accustomed to maximizing revenue through extended stays and additional services may not immediately adapt to a system that rewards efficiency over volume. The study suggests that without stronger incentives or regulatory oversight, the PDP model alone might fall short of fully optimizing resource allocation. In City W, where healthcare facilities often grapple with limited staff and infrastructure, the transition to a more streamlined approach faces additional barriers, as providers may prioritize patient throughput over systemic change.

To address these behavioral challenges, complementary strategies beyond payment reform appear necessary to reinforce the goals of efficiency. Initiatives such as standardized discharge planning protocols or performance-based incentives could help align hospital practices with the intended outcomes of PDP. Training programs for medical staff on efficient care delivery, coupled with clear guidelines on appropriate lengths of stay for psychiatric conditions, might further support this shift. Without such measures, the risk persists that hospitals will find workarounds within the PDP framework, undermining efforts to reduce unnecessary utilization. The experience in City W highlights that payment reforms, while powerful, must be part of a broader ecosystem of policy tools to truly transform service delivery in mental health care.

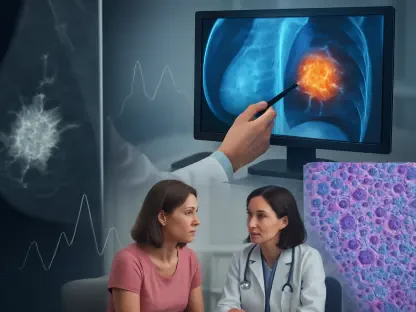

Quality of Care Post-Reform

Improvements in Readmission Rates

A particularly encouraging outcome of the PDP reform in City W is the notable improvement in 30-day all-cause readmission rates, a key indicator of care quality and coordination. Prior to the reform, both primary and secondary hospitals experienced a troubling upward trend in readmissions, with monthly increases of 0.017% and 0.018%, respectively, under the FFS system. This pattern often signaled gaps in post-discharge support or premature releases driven by financial pressures. Following the PDP rollout, these trends reversed significantly, with primary hospitals seeing a monthly decline of 0.029% and secondary hospitals a decrease of 0.018%. Such progress suggests that the reform’s design, which includes disincentives for frequent readmissions, has motivated providers to focus on effective treatment and follow-up care.

This positive shift in readmission rates points to enhanced care coordination as a direct benefit of the PDP model. By reducing financial rewards for multiple admissions within a short timeframe, the system appears to encourage hospitals to invest in discharge planning and outpatient support, ensuring patients achieve stability before leaving care. For individuals with mental disorders, who often face recurring crises, this could mean fewer disruptive cycles of hospitalization. The data from City W offers a glimpse of how payment structures can influence clinical priorities, pushing facilities to address underlying issues rather than merely treating symptoms in a revolving-door fashion. However, sustaining these gains requires ongoing vigilance to ensure they reflect genuine improvements rather than artificial suppression of necessary care.

Concerns Over Access Barriers

Despite the encouraging drop in readmission rates, a pressing concern remains that the PDP model’s cost-driven framework might inadvertently create barriers to essential re-hospitalization for patients in need. Lower readmission figures could, in some instances, indicate that individuals facing acute mental health crises are being denied timely readmission due to financial disincentives faced by hospitals. This risk is particularly acute for those with severe or recurrent conditions, where access to inpatient care during critical episodes can be lifesaving. If providers prioritize avoiding reduced reimbursements over patient well-being, the quality of care could suffer, undermining the reform’s broader goals.

Addressing these potential access barriers demands the integration of robust quality assurance programs to monitor patient outcomes under PDP. Policymakers must establish clear criteria for necessary readmissions, ensuring that cost controls do not deter hospitals from admitting patients who genuinely require intensive care. Additionally, incorporating patient feedback and clinical data into evaluations of the reform can help identify instances where access is being restricted. The experience in City W serves as a reminder that while financial efficiency is a worthy aim, it must not come at the expense of equitable access to treatment. Striking this balance is crucial, especially in mental health care, where the consequences of inadequate support can be profound and long-lasting for affected individuals and their families.

Policy Implications of PDP Reform

Tailoring Reforms to Local Needs

The implementation of PDP in City W underscores the importance of designing healthcare reforms that account for local socioeconomic conditions and infrastructure challenges. As a less economically developed region in central China, City W faces unique constraints, including limited healthcare resources and a heavy reliance on public insurance for access to care. These factors shape how PDP impacts both providers and patients, suggesting that a one-size-fits-all approach to payment reform may not yield consistent results across diverse settings. For instance, reimbursement rates under PDP must reflect the operational disparities between primary and secondary hospitals to prevent inequitable resource distribution that could widen existing gaps in care delivery.

Adapting reforms like PDP to regional realities also means recognizing that lessons from City W may not directly translate to wealthier or better-equipped areas. In regions with greater financial flexibility, hospitals might absorb cost reductions without compromising services, whereas in constrained environments, the same reductions could strain capacity. Policymakers must therefore conduct thorough assessments of local healthcare landscapes before scaling up such models, ensuring that adjustments are made to address specific needs. This tailored approach could involve tiered payment structures or additional funding for underserved areas, guaranteeing that the benefits of cost control are realized without sacrificing the ability of facilities to meet patient demands effectively.

Monitoring Unintended Consequences

Continuous evaluation of the PDP reform is essential to detect and mitigate unintended consequences that could undermine its success, particularly in the realm of mental health care where patient needs are often complex. Issues such as under-treatment, premature discharges, or restricted access to necessary re-hospitalization must be closely monitored to prevent adverse outcomes. The study from City W highlights that while cost savings and reduced readmissions are positive, they could mask deeper problems if not paired with rigorous oversight. Establishing mechanisms to track clinical outcomes and patient experiences can provide early warnings of potential pitfalls, allowing for timely interventions to correct course.

Beyond data collection, engaging with healthcare providers and patients offers valuable insights into the real-world impact of PDP. Feedback from these stakeholders can reveal whether cost pressures are leading to compromises in care quality or if certain groups are disproportionately affected by the reform. Policymakers should also consider integrating safeguards, such as appeals processes for denied readmissions or supplemental support for chronic cases, to protect vulnerable populations. The path forward requires a proactive and adaptive stance, ensuring that the drive for financial sustainability aligns with the ethical imperative to deliver compassionate, effective treatment. City W’s journey with PDP serves as a critical case study, demonstrating that ongoing refinement and vigilance are key to balancing economic and clinical priorities in healthcare policy.