The quest for sustainable manufacturing has led scientists to an unlikely workforce: single-celled organisms meticulously reprogrammed to produce some of the world’s most valuable chemicals. This burgeoning field of synthetic biology is unlocking the potential of microbes to serve as miniature, self-replicating factories, offering a green alternative to the energy-intensive and often polluting methods of traditional chemical synthesis. Central to this biological revolution is L-tryptophan, an essential amino acid whose unique molecular structure makes it the gateway to a vast catalog of important compounds, from life-saving pharmaceuticals and potent agrochemicals to common dyes and wellness supplements. By engineering the metabolic pathways of microorganisms like E. coli and baker’s yeast, researchers are not just replicating nature’s chemistry; they are enhancing it, creating highly efficient and controlled biomanufacturing platforms that promise to redefine industrial production for a new era.

Engineering the Microbial Assembly Line

Supercharging the Core Ingredient

The journey to create a high-performance microbial factory begins with maximizing the output of its core ingredient, L-tryptophan. To accomplish this, scientists engage in extensive metabolic engineering, a process of strategically rewiring the cell’s internal chemical assembly lines to channel resources directly toward the desired product. A primary focus is the shikimate pathway, the cell’s natural route for producing aromatic amino acids. Researchers have identified key bottlenecks within this pathway and have developed sophisticated techniques to overcome them. One crucial strategy involves disabling the natural feedback inhibition mechanisms, which act as safety brakes that halt production when L-tryptophan levels get too high. By modifying enzymes so they are no longer inhibited by the final product and altering the genetic switches that control pathway expression, scientists can keep the production line running at full capacity. This ensures a continuous and abundant supply of the foundational molecule, turning the microbe into a dedicated L-tryptophan powerhouse.

Furthermore, optimizing L-tryptophan production requires a holistic approach that addresses the entire metabolic network of the cell. In addition to releasing the brakes on the pathway, engineers work to boost the supply of essential raw materials, or precursors, like phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P). This is often achieved by engineering other parts of the cell’s metabolism to overproduce these key inputs. Simultaneously, competing metabolic branches that divert these valuable precursors toward the synthesis of other aromatic amino acids, such as tyrosine and phenylalanine, are blocked or downregulated. By strategically pruning these side routes, all metabolic traffic is directed toward the L-tryptophan exit. This multi-pronged approach of enhancing precursor availability, removing feedback inhibition, and eliminating competing pathways creates a highly efficient metabolic funnel, leading to dramatic, industrially significant increases in L-tryptophan yields within engineered microbial hosts.

Building a “Smart” Factory

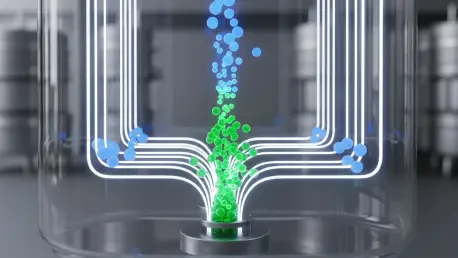

While maximizing production is crucial, forcing a microbe to operate at full throttle continuously can be counterproductive, leading to a condition known as metabolic burden. This immense stress on the cell can slow its growth, compromise its health, and ultimately limit the overall efficiency of the biomanufacturing process. To address this, the field has shifted from static, always-on pathway designs to sophisticated dynamic regulatory systems. These intelligent systems effectively install a responsive management program within the cell, allowing it to adapt its metabolic activity in real time. Using tools like transcription factor-based biosensors, the microbe can sense the internal concentration of specific molecules and adjust the expression of production-related genes accordingly. This enables the cell to intelligently balance the demands of production with the needs of its own survival, ramping up synthesis when resources are plentiful and dialing it back to conserve energy when necessary, leading to more robust and sustainable performance.

The toolkit for creating these “smart” cellular factories extends beyond simple biosensors, incorporating a variety of advanced genetic switches that offer precise control over the production process. Riboswitches, for instance, regulate gene expression at the RNA level, providing a rapid and sensitive response to changing metabolite levels. Additionally, engineers can use external triggers, such as temperature shifts or the introduction of a specific chemical inducer, to activate or deactivate production pathways at will. This temporal control allows for a separation of the growth and production phases. The microbial culture can first be grown to a high density without the stress of chemical synthesis, and once the optimal population is achieved, the production pathway can be switched on. This decoupling of growth from production mitigates metabolic burden, extends the productive lifespan of the culture, and ultimately maximizes the total yield of the target chemical, making the entire process more reliable and economically viable for industrial scale-up.

From Simple Molecules to Complex Medicines

Assembling Valuable Derivatives

Once a robust and high-yielding supply of L-tryptophan is secured, the microbial chassis becomes a versatile platform for producing a wide array of valuable downstream products. By introducing new sets of enzymes, often sourced from other organisms like plants or different microbes, scientists can extend the native metabolic pathway to synthesize a diverse portfolio of L-tryptophan derivatives. These efforts have successfully been grouped into three main classes of compounds. The first includes melatonin-associated products, such as the direct precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan, the vital neurotransmitter serotonin, and the sleep-regulating hormone melatonin itself. A second category focuses on indigo-associated products, which includes the famous blue dye indigo as well as related pigments like indirubin. The third class comprises auxin-associated products, primarily plant growth hormones like indole-3-acetic acid, which have major applications in agriculture. The successful synthesis of these compounds, often at gram-per-liter scales, showcases the power of this modular approach.

The technical achievements enabling the production of these derivatives are a testament to the sophistication of modern synthetic biology. Creating these novel pathways often requires more than simply inserting new genes; it involves a suite of advanced techniques. Protein engineering is frequently employed to improve the efficiency and stability of the newly introduced enzymes, tailoring them to function optimally within the foreign microbial host. Another key strategy is cofactor regeneration, which ensures that the helper molecules required for many enzymatic reactions are continuously recycled and available. For pathways involving toxic intermediates, engineers may use spatial compartmentalization, confining specific reactions to certain parts of the cell to protect the host from damage. These combined strategies—harnessing heterologous enzymes, enhancing protein function, and managing pathway logistics—demonstrate a mature engineering paradigm capable of transforming a simple amino acid into a range of commercially important chemicals.

Tackling Nature’s Most Complex Molecules

The true frontier of microbial biomanufacturing lies in the synthesis of highly complex natural products, particularly multi-ring alkaloids derived from strictosidine. This class includes some of the most potent anticancer agents known, such as vinblastine, which are naturally produced by plants through dozens of intricate enzymatic steps. Replicating these long and complex pathways in a simple microbe is a monumental challenge. The enzymes involved are often difficult to produce in a functional form, and the overall process requires a delicate balance of numerous intermediates. To manage this complexity, researchers adopt a modular design strategy. The lengthy pathway is broken down into smaller, more manageable segments, each of which can be optimized independently in different microbial strains before being combined into a single, functional assembly line. This divide-and-conquer approach makes the otherwise intractable problem of building these sophisticated molecular architectures achievable.

Addressing the unique demands of complex plant-based chemistry often requires moving beyond bacterial hosts like E. coli. Eukaryotic organisms, particularly the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, have proven to be far more suitable for this demanding task. Yeast cells possess internal organelles and protein-folding machinery that more closely resemble those of plants, making them better equipped to correctly express and fold complex plant enzymes. They are also more adept at handling the multi-step redox reactions that are fundamental to alkaloid biosynthesis. Even with a superior host, direct synthesis can be challenging, leading researchers to use innovative hybrid approaches like precursor feeding, where a chemically synthesized intermediate is supplied to the engineered yeast, which then performs the final, most difficult steps of the synthesis. This synergy between advanced synthetic biology and a well-chosen eukaryotic chassis is steadily paving the way for the sustainable production of nature’s most valuable and life-saving medicines.

Blueprints for a Bio-Based Future

The collective advancements in microbial engineering have illuminated a clear set of design principles for future biomanufacturing platforms. Success hinges on a trinity of strategies: meticulous control over precursor supply, the implementation of flexible and dynamic regulatory networks, and the use of modular design to construct and optimize complex pathways. These pillars have guided the transformation of simple microbes into sophisticated chemical producers. However, the journey from laboratory success to industrial-scale reality is still marked by persistent challenges. Issues such as enzyme incompatibility between different pathway modules, the inherent toxicity of some products to the host cells, and the sheer length of many desirable synthetic routes continue to be significant bottlenecks. Overcoming these hurdles will require further innovation and a deeper understanding of cellular physiology and metabolic integration.

The path forward, however, is being paved by the powerful convergence of synthetic biology with data-driven, AI-assisted design. Machine learning algorithms can now predict optimal pathway configurations, identify rate-limiting enzymes, and design novel proteins with enhanced capabilities, dramatically accelerating the engineering cycle. As these computational tools become more integrated with automated laboratory systems, the ability to design, build, and test thousands of microbial variants will become routine. This synergy promises to systematically address current limitations, closing the gap between high-titer production of simple precursors and the efficient, scalable synthesis of the most complex and valuable molecules. The era of microbial chemical factories has firmly arrived, positioning bio-based manufacturing as a cornerstone of a more sustainable global economy for health, agriculture, and industry.